Welcome to DU!

The truly grassroots left-of-center political community where regular people, not algorithms, drive the discussions and set the standards.

Join the community:

Create a free account

Support DU (and get rid of ads!):

Become a Star Member

Latest Breaking News

General Discussion

The DU Lounge

All Forums

Issue Forums

Culture Forums

Alliance Forums

Region Forums

Support Forums

Help & Search

General Discussion

Related: Editorials & Other Articles, Issue Forums, Alliance Forums, Region Forums57 Years Ago Today; "We choose to go to the moon..."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/We_choose_to_go_to_the_Moon

President John F. Kennedy speaking at Rice University on September 12, 1962

"We choose to go to the Moon" is the well-known tagline from a speech about the effort to reach the Moon delivered by United States President John F. Kennedy to a large crowd gathered at Rice Stadium in Houston, Texas on September 12, 1962. The speech was intended to persuade the American people to support the Apollo program, the national effort to land a man on the Moon.

In his speech, Kennedy characterized space as a new frontier, invoking the pioneer spirit that dominated American folklore. He infused the speech with a sense of urgency and destiny, and emphasized the freedom enjoyed by Americans to choose their destiny rather than have it chosen for them. Although he called for competition with the Soviet Union, he also proposed making the Moon landing a joint project.

The speech resonated widely and is still remembered, although at the time there was disquiet about the cost and value of the Moon-landing effort. Kennedy's goal was realized in July 1969, nearly six years after his 1963 assassination, with the successful Apollo 11 mission.

<snip>

Speech delivery

Kennedy's speech on the nation's space effort delivered at Rice Stadium on September 12, 1962

On September 12, 1962, a warm and sunny day, President Kennedy delivered his speech before a crowd of about 40,000 people in the Rice University football stadium, many of them students. The middle portion of the speech has been widely quoted, and reads as follows:

The joke referring to the Rice–Texas football rivalry was handwritten by Kennedy into the speech text, and is the part of the speech remembered by sports fans. Since then, Rice has beaten Texas in 1965 and 1994. Later in the speech Kennedy also made a joke about the heat. The jokes elicited cheers and laughter from the audience. While these side comments may have diminished the rhetorical power of the speech, and do not resonate outside Texas, they stand as a reminder of the part Texas played in the space race.

Rhetoric

The crowd at Rice University watching Kennedy's speech

Kennedy's speech used three strategies: "a characterization of space as a beckoning frontier; an articulation of time that locates the endeavor within a historical moment of urgency and plausibility; and a final, cumulative strategy that invites audience members to live up to their pioneering heritage by going to the Moon."

When addressing the crowd at Rice University, he equated the desire to explore space with the pioneering spirit that had dominated American folklore since the nation's foundation. This allowed Kennedy to reference back to his inaugural address, when he declared to the world "Together let us explore the stars". When he met with Nikita Khrushchev, the Premier of the Soviet Union in June 1961, Kennedy proposed making the Moon landing a joint project, but Khrushchev did not take up the offer. There was rhetorical opposition in the speech to extending the militarization of space.

Kennedy verbally condensed human history to fifty years, in which "only last week did we develop penicillin and television and nuclear power, and now if America's new spacecraft succeeds in reaching Venus [Mariner 2], we will have literally reached the stars before midnight tonight." With this extended metaphor, Kennedy sought to imbue a sense of urgency and change in his audience. Most prominently, the phrase "We choose to go to the Moon" in the Rice speech was repeated three times consecutively, followed by an explanation that climaxes in his declaration that the challenge of space is "one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win."

Considering the line before rhetorically asked the audience why they choose to compete in tasks that challenge them, Kennedy highlighted here the nature of the decision to go to space as being a choice, an option that the American people have elected to pursue. Rather than claim it as essential, he emphasized the benefits such an endeavor could provide – uniting the nation and the competitive aspect of it. As Kennedy told Congress earlier, "whatever mankind must undertake, free men must fully share." These words emphasized the freedom enjoyed by Americans to choose their destiny rather than have it chosen for them. Combined with Kennedy's overall usage of rhetorical devices in the Rice University speech, they were particularly apt as a declaration that began the American space race.

Kennedy was able to describe a romantic notion of space in the Rice University speech with which all citizens of the United States, and even the world could participate, vastly increasing the number of citizens interested in space exploration. He began by talking about space as the new frontier for all of mankind, instilling the dream within the audience. He then condensed human history to show that within a very brief period of time space travel will be possible, informing the audience that their dream is achievable. Lastly, he uses the first-personal plural "we" to represent all the people of the world that would allegedly explore space together, but also involves the crowd.

Reception

Kennedy attending a briefing at Cape Canaveral on September 11, 1962.

With him in the front row are (from left) NASA administrator James Webb, Vice President Lyndon Johnson, NASA Launch Center director Kurt Debus, Lieutenant General Leighton I. Davis and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara.

Paul Burka, the executive editor of Texas Monthly magazine, a Rice alumnus who was present in the crowd that day, recalled 50 years later that the speech "speaks to the way Americans viewed the future in those days. It is a great speech, one that encapsulates all of recorded history and seeks to set it in the history of our own time. Unlike today’s politicians, Kennedy spoke to our best impulses as a nation, not our worst." Ron Sass and Robert Curl were among the many members of the Rice University faculty present. Curl was amazed by the cost of the space exploration program. They recalled that the ambitious goal did not seem so remarkable at the time, and that Kennedy's speech was not regarded as so different from one delivered by President Dwight D. Eisenhower at Rice's Autry Court in 1960; but that speech has long since been forgotten, while Kennedy's is still remembered.

The speech did not stem a rising tide of disquiet about the Moon landing effort. There were many other things that the money could be spent on. Eisenhower declared, "To spend $40 billion to reach the Moon is just nuts." Senator Barry Goldwater argued that the civilian space program was pushing the more important military one aside. Senator William Proxmire feared that scientists would be diverted away from military research into space exploration. A budget cut was only narrowly averted. Kennedy gave a speech to the United Nations General Assembly on September 20, 1963, in which he again proposed a joint expedition to the Moon. Khrushchev remained cautious about participating, and responded with a statement in October 1963 in which he declared that the Soviet Union had no plans to send cosmonauts to the Moon. However, his military advisors persuaded him that the offer was a good one, as it would enable the Soviet Union to acquire American technology. Kennedy ordered reviews of the Apollo project in April, August and October 1963. The final report was received on November 29, 1963, a week after Kennedy's assassination.

Legacy

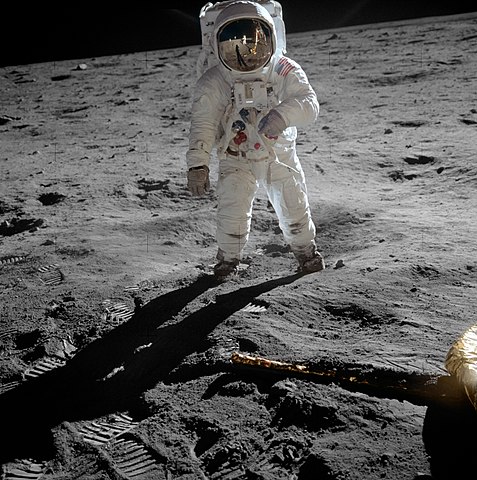

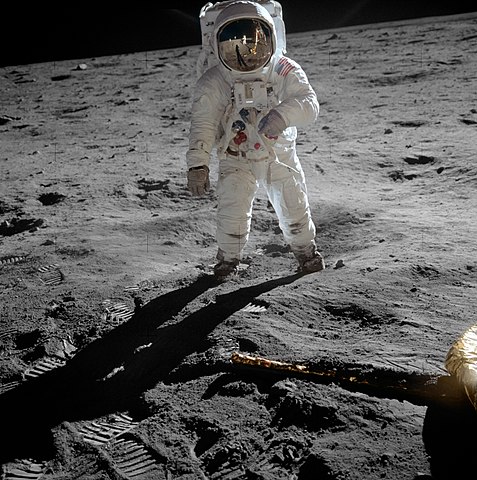

Buzz Aldrin on the Moon, 1969.

The idea of a joint Moon mission was abandoned after Kennedy's death, but the Apollo Project became a memorial to him. His goal was fulfilled in July 1969, with the successful Apollo 11 Moon landing. This accomplishment remains an enduring legacy of Kennedy's speech, but his deadline demanded a necessarily narrow focus, and there was no indication of what should be done next once it was achieved. Apollo did not usher in an era of lunar exploration, and no further missions were sent to the Moon after Apollo 17 in 1972. Subsequent planned Apollo missions were canceled. The Space Shuttle and International Space Station projects never captured the public imagination the way the Apollo Project did, and NASA would struggle to realize its visions with inadequate resources. Ambitious visions of space exploration were proclaimed by Presidents George H. W. Bush in 1989, George W. Bush in 2004, and Donald J. Trump in 2017, but the future of the American space program remains uncertain.

</snip>

President John F. Kennedy speaking at Rice University on September 12, 1962

"We choose to go to the Moon" is the well-known tagline from a speech about the effort to reach the Moon delivered by United States President John F. Kennedy to a large crowd gathered at Rice Stadium in Houston, Texas on September 12, 1962. The speech was intended to persuade the American people to support the Apollo program, the national effort to land a man on the Moon.

In his speech, Kennedy characterized space as a new frontier, invoking the pioneer spirit that dominated American folklore. He infused the speech with a sense of urgency and destiny, and emphasized the freedom enjoyed by Americans to choose their destiny rather than have it chosen for them. Although he called for competition with the Soviet Union, he also proposed making the Moon landing a joint project.

The speech resonated widely and is still remembered, although at the time there was disquiet about the cost and value of the Moon-landing effort. Kennedy's goal was realized in July 1969, nearly six years after his 1963 assassination, with the successful Apollo 11 mission.

<snip>

Speech delivery

Kennedy's speech on the nation's space effort delivered at Rice Stadium on September 12, 1962

On September 12, 1962, a warm and sunny day, President Kennedy delivered his speech before a crowd of about 40,000 people in the Rice University football stadium, many of them students. The middle portion of the speech has been widely quoted, and reads as follows:

We set sail on this new sea because there is new knowledge to be gained, and new rights to be won, and they must be won and used for the progress of all people. For space science, like nuclear science and all technology, has no conscience of its own. Whether it will become a force for good or ill depends on man, and only if the United States occupies a position of pre-eminence can we help decide whether this new ocean will be a sea of peace or a new terrifying theater of war. I do not say that we should or will go unprotected against the hostile misuse of space any more than we go unprotected against the hostile use of land or sea, but I do say that space can be explored and mastered without feeding the fires of war, without repeating the mistakes that man has made in extending his writ around this globe of ours.

There is no strife, no prejudice, no national conflict in outer space as yet. Its hazards are hostile to us all. Its conquest deserves the best of all mankind, and its opportunity for peaceful cooperation may never come again. But why, some say, the Moon? Why choose this as our goal? And they may well ask, why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years ago, fly the Atlantic? Why does Rice play Texas?

We choose to go to the Moon! We choose to go to the Moon...We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win, and the others, too.

The joke referring to the Rice–Texas football rivalry was handwritten by Kennedy into the speech text, and is the part of the speech remembered by sports fans. Since then, Rice has beaten Texas in 1965 and 1994. Later in the speech Kennedy also made a joke about the heat. The jokes elicited cheers and laughter from the audience. While these side comments may have diminished the rhetorical power of the speech, and do not resonate outside Texas, they stand as a reminder of the part Texas played in the space race.

Rhetoric

The crowd at Rice University watching Kennedy's speech

Kennedy's speech used three strategies: "a characterization of space as a beckoning frontier; an articulation of time that locates the endeavor within a historical moment of urgency and plausibility; and a final, cumulative strategy that invites audience members to live up to their pioneering heritage by going to the Moon."

When addressing the crowd at Rice University, he equated the desire to explore space with the pioneering spirit that had dominated American folklore since the nation's foundation. This allowed Kennedy to reference back to his inaugural address, when he declared to the world "Together let us explore the stars". When he met with Nikita Khrushchev, the Premier of the Soviet Union in June 1961, Kennedy proposed making the Moon landing a joint project, but Khrushchev did not take up the offer. There was rhetorical opposition in the speech to extending the militarization of space.

Kennedy verbally condensed human history to fifty years, in which "only last week did we develop penicillin and television and nuclear power, and now if America's new spacecraft succeeds in reaching Venus [Mariner 2], we will have literally reached the stars before midnight tonight." With this extended metaphor, Kennedy sought to imbue a sense of urgency and change in his audience. Most prominently, the phrase "We choose to go to the Moon" in the Rice speech was repeated three times consecutively, followed by an explanation that climaxes in his declaration that the challenge of space is "one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win."

Considering the line before rhetorically asked the audience why they choose to compete in tasks that challenge them, Kennedy highlighted here the nature of the decision to go to space as being a choice, an option that the American people have elected to pursue. Rather than claim it as essential, he emphasized the benefits such an endeavor could provide – uniting the nation and the competitive aspect of it. As Kennedy told Congress earlier, "whatever mankind must undertake, free men must fully share." These words emphasized the freedom enjoyed by Americans to choose their destiny rather than have it chosen for them. Combined with Kennedy's overall usage of rhetorical devices in the Rice University speech, they were particularly apt as a declaration that began the American space race.

Kennedy was able to describe a romantic notion of space in the Rice University speech with which all citizens of the United States, and even the world could participate, vastly increasing the number of citizens interested in space exploration. He began by talking about space as the new frontier for all of mankind, instilling the dream within the audience. He then condensed human history to show that within a very brief period of time space travel will be possible, informing the audience that their dream is achievable. Lastly, he uses the first-personal plural "we" to represent all the people of the world that would allegedly explore space together, but also involves the crowd.

Reception

Kennedy attending a briefing at Cape Canaveral on September 11, 1962.

With him in the front row are (from left) NASA administrator James Webb, Vice President Lyndon Johnson, NASA Launch Center director Kurt Debus, Lieutenant General Leighton I. Davis and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara.

Paul Burka, the executive editor of Texas Monthly magazine, a Rice alumnus who was present in the crowd that day, recalled 50 years later that the speech "speaks to the way Americans viewed the future in those days. It is a great speech, one that encapsulates all of recorded history and seeks to set it in the history of our own time. Unlike today’s politicians, Kennedy spoke to our best impulses as a nation, not our worst." Ron Sass and Robert Curl were among the many members of the Rice University faculty present. Curl was amazed by the cost of the space exploration program. They recalled that the ambitious goal did not seem so remarkable at the time, and that Kennedy's speech was not regarded as so different from one delivered by President Dwight D. Eisenhower at Rice's Autry Court in 1960; but that speech has long since been forgotten, while Kennedy's is still remembered.

The speech did not stem a rising tide of disquiet about the Moon landing effort. There were many other things that the money could be spent on. Eisenhower declared, "To spend $40 billion to reach the Moon is just nuts." Senator Barry Goldwater argued that the civilian space program was pushing the more important military one aside. Senator William Proxmire feared that scientists would be diverted away from military research into space exploration. A budget cut was only narrowly averted. Kennedy gave a speech to the United Nations General Assembly on September 20, 1963, in which he again proposed a joint expedition to the Moon. Khrushchev remained cautious about participating, and responded with a statement in October 1963 in which he declared that the Soviet Union had no plans to send cosmonauts to the Moon. However, his military advisors persuaded him that the offer was a good one, as it would enable the Soviet Union to acquire American technology. Kennedy ordered reviews of the Apollo project in April, August and October 1963. The final report was received on November 29, 1963, a week after Kennedy's assassination.

Legacy

Buzz Aldrin on the Moon, 1969.

The idea of a joint Moon mission was abandoned after Kennedy's death, but the Apollo Project became a memorial to him. His goal was fulfilled in July 1969, with the successful Apollo 11 Moon landing. This accomplishment remains an enduring legacy of Kennedy's speech, but his deadline demanded a necessarily narrow focus, and there was no indication of what should be done next once it was achieved. Apollo did not usher in an era of lunar exploration, and no further missions were sent to the Moon after Apollo 17 in 1972. Subsequent planned Apollo missions were canceled. The Space Shuttle and International Space Station projects never captured the public imagination the way the Apollo Project did, and NASA would struggle to realize its visions with inadequate resources. Ambitious visions of space exploration were proclaimed by Presidents George H. W. Bush in 1989, George W. Bush in 2004, and Donald J. Trump in 2017, but the future of the American space program remains uncertain.

</snip>

...and, Happy 66th wedding anniversary Jack and Jackie!!

InfoView thread info, including edit history

TrashPut this thread in your Trash Can (My DU » Trash Can)

BookmarkAdd this thread to your Bookmarks (My DU » Bookmarks)

1 replies, 615 views

ShareGet links to this post and/or share on social media

AlertAlert this post for a rule violation

PowersThere are no powers you can use on this post

EditCannot edit other people's posts

ReplyReply to this post

EditCannot edit other people's posts

Rec (3)

ReplyReply to this post

1 replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

= new reply since forum marked as read

Highlight:

NoneDon't highlight anything

5 newestHighlight 5 most recent replies

57 Years Ago Today; "We choose to go to the moon..." (Original Post)

Dennis Donovan

Sep 2019

OP

Vinca

(50,237 posts)1. Now THAT was a President.

And what an exciting time in history he began.