General Discussion

Related: Editorials & Other Articles, Issue Forums, Alliance Forums, Region ForumsDid you know that MS Stockholm, the ship that collided with SS Andrea Doria 1956, is still sailing?

She's now known as MV Astoria, and has been heavily refitted, but she still plies the ocean:

MV Astoria was constructed as an ocean liner and subsequently rebuilt as a cruise ship. She was ordered in 1944, and launched 9 September 1946, as Stockholm by Götaverken in Gothenburg for the Swedish America Line (SAL). She made her Maiden voyage in 1948, under the command of captain John Nordlander. During her seven decades of service she has passed through several owners and sailed under the names Völkerfreundschaft, Volker, Fridtjof Nansen, Italia I, Italia Prima, Valtur Prima, Caribe, Athena, and Azores before beginning service as Astoria in March 2016.

As Stockholm, she was best known for an accidental collision with Andrea Doria in 1956, resulting in the sinking of the latter ship and 46 fatalities.

About the collision with SS Andrea Doria:

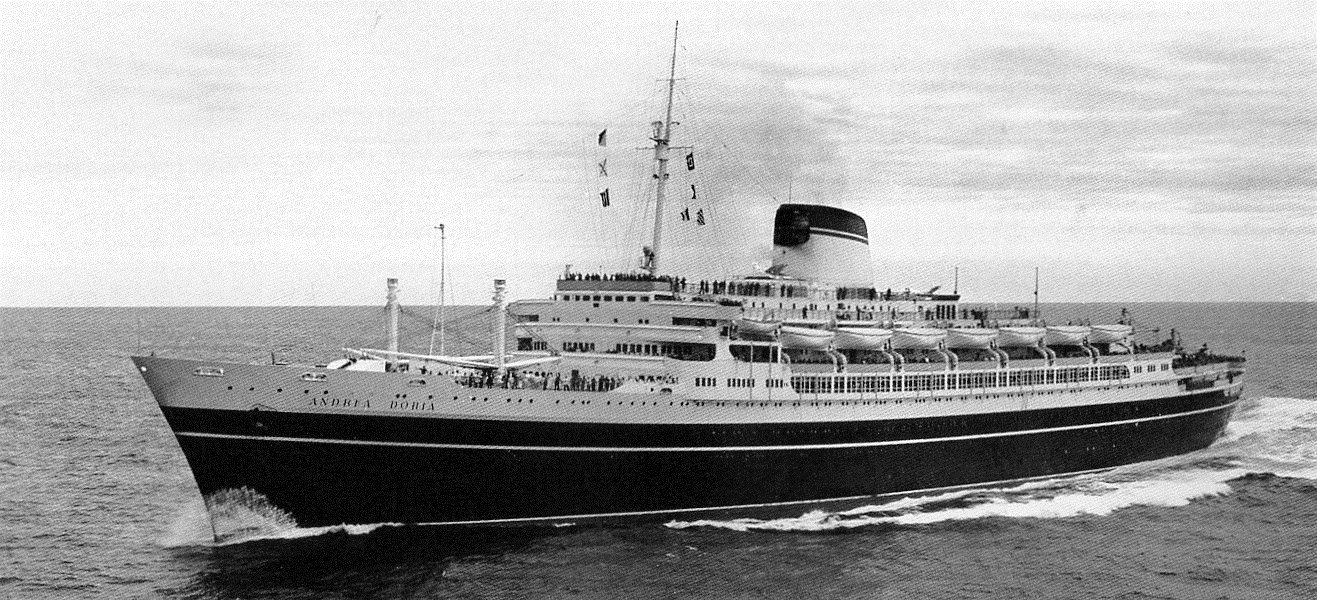

SS Andrea Doria

Final voyage

A collision course

The 51st westbound crossing of the Andrea Doria to New York began as a typical run on the North Atlantic. Her most recent eastbound crossing from New York had concluded on 14 July, and after a three-day turnaround the ship was prepared to make another trek across the Atlantic, which was scheduled to begin from Genoa on Tuesday, 17 July. On this run she was booked to roughly 90% of her total passenger capacity with 1,134 passengers travelling aboard her; 190 in First Class, 267 in Cabin Class and 677 in Tourist Class, which in addition to her crew of 572 would add up to a total of 1,706 persons aboard.

On the morning of 17 July, boarding at the pier at Genoa began at 8 AM, as the Doria took on her first batch of passengers. In all, 277 passengers embarked at Genoa; 49 First Class, 72 Cabin Class and 156 Tourist Class. Among those boarding in First Class were Hungarian ballet dancers Istvan Rabovsky and Nora Kovach, who had defected from the Soviet bloc to the United States just three years earlier. The Doria departed Genoa at 11 AM on the first leg of her journey.

Her first port of call was at Cannes, on the French Riviera, where she arrived about mid afternoon that same day. Only a handful of passengers boarded here, 48 in all; 30 First Class, 15 Cabin Class and only 3 Tourist Class. Among them was one of the Doria's most famous passengers, Hollywood actress Ruth Roman, who was travelling with her three-year-old son Richard. From Cannes the Doria then proceeded on the next part of her crossing, which led her 400 nautical miles (700 km) to the southeast to Naples, where she arrived later the following morning to take on the bulk of her passengers. A total of 744 came aboard at Naples; another 85 in First Class, 161 in Cabin Class and 498 in Tourist Class, most of the latter were Italian immigrants from impoverished regions of southern Italy on their way to new lives in America. She departed Naples just after 6 PM that evening[14], making her final port of call two days later while dropping anchor off Gibraltar. After collecting her final 65 passengers (26 First Class, 19 Cabin Class, 20 Tourist Class), she proceeded onto the open Atlantic for New York.

On Wednesday, 25 July, just before noon, MS Stockholm, a passenger liner of the Swedish American Line, departed New York Harbor on her 103rd eastbound crossing across the Atlantic to her home port of Gothenburg, Sweden. At 12,165 tons and 160 metres (525 ft) in length, roughly half the size of Andrea Doria, Stockholm was the smallest passenger liner on the North Atlantic run during the 1950s. Completed in 1948, Stockholm was of a much more practical design compared to Andrea Doria. Originally built to accommodate only 395 passengers in two classes, Stockholm was designed more for comfort than the luxury and opulence found aboard Andrea Doria. The main reason for this was that the Swedish-American Line was aware that the age of Trans-Atlantic passenger travel was coming to an end with the rapid growth of air travel. However, what they did not envision was the massive surge in tourism which arose during the 1950s. This resulted in the Swedish-American Line's decision to withdraw Stockholm from service in 1953 for an overhaul which included an addition to her superstructure to provide space for accommodations for an additional 153 passengers, increasing her maximum passenger capacity to 548. This proved to be a successful move, as by 1956 Stockholm had gained a worthy reputation on the North Atlantic. On this voyage, she left New York almost booked to capacity with 534 passengers and a crew of 208, a total of 742 people aboard. She was commanded by Captain Harry Gunnar Nordenson, though Third Officer Johan-Ernst Carstens-Johannsen was on duty on the bridge at the time of the accident. Stockholm was following its usual course east to Nantucket Lightship, making about 18 knots (33 km/h) with clear skies. Carstens estimated visibility at 6 nautical miles (11 km).

As Stockholm and Andrea Doria were approaching each other head-on, in the heavily used shipping corridor, the westbound Andrea Doria had been traveling in heavy fog for hours. The captain had reduced speed slightly from 23.0 to 21.8 knots (42.6 to 40.4 km/h), activated the ship's fog-warning whistle, and had closed the watertight doors, all customary precautions while sailing in such conditions. However, the eastbound Stockholm had yet to enter what was apparently the edge of a fog bank and was seemingly unaware of it and the movement of the other ship hidden in it. The waters of the North Atlantic south of Nantucket Island are frequently the site of intermittent fog as the cold Labrador Current encounters the Gulf Stream.

As the two ships approached each other, at a combined speed of 40 knots (74 km/h), in failing light, each was aware of the presence of another ship; but guided only by radar they apparently misinterpreted each other's course. No radio communication was made between the two ships, at first.

The original inquiry established that in the critical minutes before the collision, Andrea Doria gradually steered to its left, attempting a starboard-to-starboard passing, while Stockholm turned about 20° to its right, an action intended to widen the passing distance of a port-to-port passing. In fact, they were actually steering towards each other – narrowing, rather than widening, the passing distance. As a result of the extremely thick fog that enveloped Andrea Doria as the ships approached each other, the ships were quite close by the time visual contact was established. By then, the crews realized that they were on a collision course, but despite last-minute maneuvers, they could not avoid the collision.

In the last moments before impact, Stockholm turned hard to starboard (right) and was in the process of reversing her propellers, attempting to stop. Andrea Doria, remaining at her cruising speed of almost 22 knots (41 km/h) engaged in a hard turn to port (left), her captain hoping to outrun the collision. Around 11:10 pm, the two ships collided, Stockholm striking the side of Andrea Doria.

Impact and penetration

SS Andrea Doria the morning after the collision with the MS Stockholm in fog off Nantucket Island: The hole in her starboard side from the collision with Stockholm is visible near the waterline about one-third aft of the bow.

When Andrea Doria and Stockholm collided at almost a 90° angle, Stockholm's sharply raked ice breaking prow pierced Andrea Doria's starboard side about one-third of her length from the bow. It penetrated the hull to a depth of nearly 40 feet (12 m), and the keel. Below the waterline, five fuel tanks on Andrea Doria's starboard side were torn open, and they filled with thousands of tons of seawater. Meanwhile, air was trapped in the five empty tanks on the port side, causing them to float more readily, contributing to a severe list. The ship's large fuel tanks were mostly empty at the time of the collision, since the ship was nearing the end of her voyage, but all the empty fuel tanks did was further increase the list.

26 July 1956: After colliding with Andrea Doria, Stockholm with severely damaged prow, heads to New York.

Andrea Doria was designed with her hull divided into 11 watertight compartments, separated by steel bulkheads which ran across the width of her hull, rising from the bottom of the ship's hull up to A Deck. The only openings in the bulkheads were on the bottom deck, where watertight doors were installed for use by the engine crew and could be easily closed in an emergency. Her design specified that if any two adjacent compartments out of any of her 11 watertight compartments were breached, she could remain afloat. In addition, following the rules and guidelines set by the International Conference for Safety of Life at Sea of 1948, Andrea Doria was also designed to take a list, even under the worst imaginable circumstances, no more than 15°. However, the combination of the five flooded tanks on one side and the five empty tanks on the other left Andrea Doria with a list which within a few minutes of the collision exceeded 20°. While the collision itself penetrated only one of Andrea Doria's watertight compartments, the severe list would gradually pull the tops of the bulkheads along the starboard side below the level of the water, allowing seawater to flow down corridors, down stairwells, and any other way it could find into the next compartment in line. In addition, the collision had also torn into an access tunnel which ran from the generator room, which was located in the compartment directly aft of where the collision had happened, to a small room at the forward end of the tank compartment which contained the controls for the pumps for the tanks. It was here that there was a fatal flaw in Andrea Doria's design, as at the point where the tunnel went through the bulkhead separating the two compartments, no watertight door was present. This allowed the generator room to flood rapidly, contributing to not only an increase in flooding, but also to a loss of electricity to the stricken liner.

Initial radio distress calls were sent out by each ship, and in that manner, they learned each other's identities. Soon afterwards, the messages were received by numerous radio and Coast Guard stations along the New England coast, and the world soon became aware that two large ocean liners had collided.

This was the SOS sent by Andrea Doria:

"SOS DE ICEH [this is Andrea Doria] SOS HERE AT 0320 GMT LAT. 40.30 N 69.53 W NEED IMMEDIATE ASSISTANCE"

Assessing damage and imminent danger

Immediately after the collision, Andrea Doria began to take on water and started to list severely to starboard. Within minutes, the list was at least 18°. After the ships separated, Captain Calamai quickly brought the engine controls to "all stop". One of the watertight doors to the engine room may have been missing, though this issue was later determined to be moot. Much more importantly, however, crucial stability was lost by the earlier failure, during routine operations, to ballast the mostly empty fuel tanks as the builders had specified. (Filling the tanks with seawater as the fuel was emptied would have resulted in more costly procedures to refuel when port was reached.) Owing to the immediate rush of seawater flooding the starboard tanks, and because the port tanks had emptied during the crossing, the list was greater than would otherwise have been the case. As it increased over the next few minutes to 20° or more, Calamai realized no hope was left for his ship unless the list could be corrected.

In the engine room, engineers attempted to pump water out of the flooding starboard tanks to no avail. Only a small amount of fuel remained, and the intakes to pump seawater into the port tanks were now high out of the water, making any attempt to level the ship futile.

Aboard Stockholm, roughly 30 feet (10 m) of her bow had been crushed and torn away. Initially, the ship was dangerously down by the bow, but emptying the freshwater tanks soon raised the bow to within 4 inches (10 cm) of normal. A quick survey determined that the major damage did not extend aft beyond the bulkhead between the first and second watertight compartments. Thus, despite being down at the bow, and having its first watertight compartment flooded, the ship was soon determined to be stable and in no imminent danger of sinking.

Rescue operations

On Andrea Doria, the decision to abandon ship was made within 30 minutes of impact. A sufficient number of lifeboats for all of the passengers and crew were positioned on each side of the Boat Deck. Procedures called for lowering the lifeboats to be fastened alongside the glass-enclosed Promenade Deck (one deck below), where evacuees could step out of windows directly into the boats, which would then be lowered down to the sea. However, it was soon determined that half of the lifeboats, those on the port side, were unlaunchable due to the severe list, which left them high in the air. To make matters worse, the list also complicated normal lifeboat procedures on the starboard side. Instead of loading lifeboats at the side of the Promenade Deck and then lowering them into the water, it would be necessary to lower the boats empty, and somehow get evacuees down the exterior of the ship to water level to board. This was eventually accomplished through ropes and Jacob's ladders. In fear of causing a panic and stampeding of the starboard lifeboats, Captain Calamai decided against giving the order to abandon ship until help arrived. In the meantime, Second Officer Badano made announcements over the loudspeaker system instructing passengers to put on their lifebelts and go to their designated muster stations.

A distress message was relayed to other ships by radio, making it clear that additional lifeboats were urgently needed. The first ship to respond to Andrea Doria's distress call was the 120-metre (390 ft) freighter Cape Ann of the United Fruit Company, which was returning to the United States after a trip to Bremerhaven, Germany. Upon receiving the message from the stricken Andrea Doria, Captain Joseph Boyd immediately set course for the site of the collision. With a crew of 44 aboard and only two 40-person lifeboats, the assistance Cape Ann could offer was limited, but within minutes, she was joined by other ships heeding the distress call. The US Navy transport USNS Private William H. Thomas, en route to New York from Livorno, Italy, with 214 troops and dependents also responded to the signal and made immediate progress towards the site. Her captain, John Shea, was placed in charge of the rescue operation by the US Navy and readily ordered his crew to prepare their eight usable lifeboats. Also joining the rescue were the US Navy destroyer escort USS Edward H. Allen and the US Coast Guard Cutter USCGC Legare (WSC-144).

81 km (44 nmi) east of the collision site, the French Line's SS Île de France was eastbound from New York en route to her home port of Le Havre, France, with 940 passengers and a crew of 826 aboard. At 44,500 tons and 225 metres (739 ft) in length, the 30-year-old luxury liner was among the largest passenger liners on the North Atlantic run. On that voyage, having left New York the same day as Stockholm, she was under the command of Captain Raoul de Beaudean, a well-respected veteran of the seas who had served the French Line for 35 years. Upon hearing of the collision and the distress call, de Beaudean was at first skeptical of the thought of a modern ship like Andrea Doria actually foundering, and knew that if he did steer back to the collision site only to find that Île de France was not needed, it would mean having to return to New York to refuel and delaying her passengers, which could have been a financial disaster for the French Line. At the same time, he knew that if his services were needed, the French Line would not question his actions in that case. Captain de Beaudean made an attempt to contact Andrea Doria to learn more about the situation, which was unsuccessful, but after making contact with Stockholm, Cape Ann, and Thomas, he quickly realized the severity of the situation and that the lives of over 1,600 people were at risk. He quickly turned Île de France around and set a direct course for the stricken Andrea Doria.

On board Andrea Doria, the launching of the eight usable lifeboats on the starboard side was yet another calamity of the night, as many of the boats left Andrea Doria only partially loaded with about 200 panicked crewmen and very few passengers.

While other ships nearby were en route, Captain Nordenson of Stockholm, having determined that his ship was not in any imminent danger of sinking, and after being assured of the safety of his mostly sleeping passengers, sent some of his lifeboats to supplement the starboard boats from Andrea Doria. In the first hours, many survivors transported by lifeboats from both ships were taken aboard Stockholm. Unlike the Titanic tragedy 44 years earlier, several other nonpassenger ships that heard Andrea Doria's SOS signal steamed as fast as they could, some eventually making it to the scene. Radio communications included relays from the other ships as Andrea Doria's radios had limited range. The United States Coast Guard from New York City also coordinated on land.

Arriving at the scene less than three hours after the collision, as he neared, Captain de Beaudean became concerned about navigating his huge ship safely between the two damaged liners, other responding vessels, lifeboats, and possibly even people in the water. Then, just as Île de France arrived, the fog lifted, and he was able to position his ship in such a way that the starboard side of Andrea Doria was somewhat sheltered. He ordered all exterior lights of Île de France to be turned on. The sight of the illuminated Île de France was a great emotional relief to many participants, crew and passengers alike.

Île de France managed to rescue the bulk of the remaining passengers by shuttling its 10 lifeboats back and forth to Andrea Doria, and receiving lifeboat loads from those of the other ships already at the scene (as well as the starboard boats from Andrea Doria). Some passengers on Île de France gave up their cabins to be used by the wet and tired survivors. Many other acts of kindness were reported by grateful survivors.

In all, 1,663 passengers and crew had been rescued from Andrea Doria. The badly damaged Stockholm, through the use of both her own lifeboats and those from the stricken Andrea Doria, took on a total of 545 survivors, of whom 234 were crew members from Andrea Doria; 129 survivors had been rescued by Cape Ann, 159 by Pvt. William H. Thomas, 77 by Edward H. Allen, including Captain Calamai and his officers, and one very fortunate American sailor who slept through the entire collision and evacuation had been lucky enough to be rescued from the abandoned, sinking liner by the tanker Robert E. Hopkins. Île de France undoubtedly played the largest role in the rescue, having taken on a total of 753 survivors.

Shortly after daybreak, the four-year-old Italian girl and four seriously injured Stockholm crewmen were airlifted from that ship at the scene by helicopters sent by the Coast Guard and U.S. Air Force. A number of passengers and some crew were hospitalized upon arrival in New York.

Andrea Doria capsizes and sinks

Andrea Doria awaiting her impending fate the morning after the collision in the Atlantic Ocean, 26 July 1956

Once the evacuation was complete, Captain Calamai of Andrea Doria shifted his attention to the possibility of towing the ship to shallow water. However, it was clear to those watching helplessly at the scene that the stricken ocean liner was doomed.

After all the survivors had been transferred onto various rescue ships bound for New York, Andrea Doria's remaining crew began to disembark – forced to abandon the ship. By 9:00 am, even Captain Calamai was in a rescue boat. The sinking began at 9:45 am and by 10:00 that morning Andrea Doria was on its side at a right angle to the sea. The starboard side dipped into the ocean and the three swimming pools were seen refilling with water. As the bow slid under, the stern rose slightly, and the port propeller and shaft became visible. As the port side slipped below the waves, some of the unused lifeboats snapped free of their davits and floated upside-down in a row. It was recorded that Andrea Doria finally sank bow first 11 hours after the collision, at 10:09 am on 26 July 1956. The ship had drifted 1.58 nautical miles (2.93 km) from the point of the collision in those 11 hours. Aerial photography of the stricken ocean liner capsizing and sinking won a Pulitzer Prize in 1957 for Harry A. Trask of the Boston Traveler newspaper.

Another interesting thing about the incident, the "miracle girl" of the collision, Linda Morgan, became the First Lady of San Antonio:

Linda Morgan (born 1942), now known as Linda Hardberger, became known as the "miracle girl" following the collision of two large passenger ships in the North Atlantic Ocean on the foggy night of July 25, 1956.

The 14-year-old girl, born in Mexico City, Mexico, was sharing a two-bed cabin with her younger half-sister on the S.S. Andrea Doria en route from Gibraltar when the ship was struck broadside by the prow of the MS Stockholm near Nantucket. During the collision, she was somehow lifted out of her bed and onto the Stockholm's crushed bow, landing safely behind a bulwark as the two ships scraped past each other before separating as the fatally-stricken Andrea Doria disappeared back into the fog.

Morgan shortly after her rescue from the wreckage.

In the ensuing confusion, a Stockholm crewman heard her calling for her mother in Spanish, an unusual language on the Swedish ship. A crewman who spoke Spanish was able to translate. The teen apparently was first to grasp what must have happened, saying to 36-year-old Bernabe Polanco Garcia: "I was on the Andrea Doria. Where am I now?"

Eight-year-old Joan Cianfarra, the sister sleeping on the adjoining bed in Linda's cabin was killed. Her step-father, Camille Cianfarra, a longtime foreign correspondent for The New York Times, stationed in Spain, was also killed in the adjacent cabin he shared with the girls' mother. They were two of 46 passengers and crew who died in the impact areas on the two ships. After all the surviving passengers and crew were evacuated by several rescue ships (most notably the S.S. Ile de France), the Andrea Doria capsized and sank the next morning. With ships of several nations transporting survivors, communication of news to the waiting families was difficult. Linda Morgan and her younger sister were both listed among missing passengers in the early reports.

Linda's father, ABC Radio Network news commentator Edward P. Morgan, was based in New York City. On his daily broadcast, he reported a memorable account of the collision of the ocean liners, not telling his thousands of listeners that his daughter had been aboard the Andrea Doria and was believed to have been killed.

Linda, who suffered a broken arm, was quickly dubbed the "miracle girl" by the news media as the story of her survival and the circumstances spread. She returned to New York City aboard the crippled Stockholm, where she was reunited with her mother Jane Cianfarra, who had been severely injured in the cabin where her husband had died, and her father. Edward Morgan then made another memorable broadcast less able to conceal his emotions, describing the difference between reporting the news about strangers and his own loved ones, and describing also the extremes of despair, joy, and gratitude that he had experienced.

Linda Morgan was admitted to St. Vincent's Hospital in New York, where her broken arm was placed in traction. When Polanco, her Spanish-speaking crewman benefactor, was on a weekend leave from the Stockholm, he went to the hospital to pay a visit. Sister Loretta Bernard, administrator of the hospital, gave Polanco a Miraculous Medal Of Our Lady. Then Linda's father, who had also worked in Mexico, greeted him with a hearty embrace. "Hombre, hombre" said Mr. Morgan, "Man, man how can I ever thank you?"

The young teenager suffered from survivor's guilt, as her stepfather and younger half-sister had been killed, and her mother grievously injured, while she had been spared. Linda moved to San Antonio, Texas in 1970. Her husband since 1968, Phil Hardberger, became Mayor of San Antonio in June 2005.

To me, this is amazing stuff.

greatauntoftriplets

(175,729 posts)I like it so much more than those monstrous things that they build these days.

Dennis Donovan

(18,770 posts)MV Astoria looks a far sight better than her contemporaries.

Today's ocean liners / cruise ships are fuggly as hell. They're condos with hulls. ![]()

greatauntoftriplets

(175,729 posts)Dennis Donovan

(18,770 posts)She was still cruising up until 2001. 9/11 crushed the cruise industry and she was a casualty.

After being laid up for several years, she was brought to the sad beach of Alang, India, but didn't quite make it to shore:

![]()

On edit: I posted about her 9 years ago?

https://www.democraticunderground.com/discuss/duboard.php?az=view_all&address=389x8550591

![]()

greatauntoftriplets

(175,729 posts)I like that the smokestacks at least look unchanged. It at least was tasteful!

Dennis Donovan

(18,770 posts)

I dunno, it definitely attracts attention!

greatauntoftriplets

(175,729 posts)kskiska

(27,045 posts)I also remember, as a child, driving with my family down the West Side Highway and seeing all the trans-Atlantic liners in a row, including the Andrea Doria. It was very exciting.

Dennis Donovan

(18,770 posts)...so much so that I named my latest boat "Normandie" after the most beautiful of transatlantic liners. I'm typing this aboard her now. ![]()

My family visited NYC in 1977 (for me, it was the first time in NYC). I was 12 and bee-lined it to the superpiers off 48th St (causing consternation with my Mom, since I ventured off on my own ![]() ). I went to Pier 88, where Normandie met her fate in 1942. I approached a PA cop, breathlessly asked him where Normandie was (he took my statement to be in the present-tense?). He said to me, "Son, Normandie's been gone for over 30 years!" I caught my breath, and thanked him.

). I went to Pier 88, where Normandie met her fate in 1942. I approached a PA cop, breathlessly asked him where Normandie was (he took my statement to be in the present-tense?). He said to me, "Son, Normandie's been gone for over 30 years!" I caught my breath, and thanked him. ![]()

Response to Dennis Donovan (Original post)

AllaN01Bear This message was self-deleted by its author.

panader0

(25,816 posts)to Honolulu. I was 11 at the time. I remember there being so many

paper streamers thrown from the ship to the dock in S.F. that I didn't

think we'd be able to pull away. It was a lot of fun.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_Lurline_(1932)

Karadeniz

(22,474 posts)MicaelS

(8,747 posts)Dennis Donovan

(18,770 posts)