Environment & Energy

Related: About this forumJevons: a 19th Century Zeno

In the 5th Century BCE a Greek philosopher, Zeno of Elea, concocted a series of paradoxes. In essence, they were all the same paradox (but let’s give him credit for more—he did put in a lot of work.)

The core of his most famous paradox has to do with traveling a given distance. Say you wish to walk out of a room where someone is discussing Jevons’ Paradox. The door is 16 feet away. First, you must walk 8 feet toward the door (half way), then 4 feet (half the remaining distance), then 2 feet and so on. The result is an "infinite progression" 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 …

Zeno’s proposition was that there is an infinite number of distances to be traveled, each of them half the distance of the previous one, and each of them takes some time to accomplish, therefore, you can never leave the room. Diogenes of Sinope supposedly proved Zeno’s conclusion false by standing up and walking.

Clearly, Zeno’s conclusion was false. (Even Zeno knew this.) However, Zeno works like a magician, distracting us with what appears to be logic, “Hmmm… you know… he might have something there… there is an infinite number of tasks to be accomplished…”

Jevons’ Paradox is akin to Zeno’s Paradoxes, but goes them one better. You see, while Zeno might have proposed that we can never truly save any energy, the proponents of Jevons’ Paradox propose that by saving energy, we actually use more!

Let’s try a quick thought experiment, following Jevon’s Paradox through. Let’s say I change all of the light bulbs in my house from incandescent bulbs to LED’s. Over time, this will save me a certain amount of money in energy costs. Let’s say it saves me $100. Jevons’ proponents say I will spend that $100, some of it I will spend by lighting my house more (since I can now afford to) and the rest I will spend on other things, like maybe my membership to DU.

Naturally, if I give money to DU, some of it will go to pay for things like servers, which require energy to run, some will go to an ISP, which requires energy to pump data through the internet, and some of it will go into the pockets of the admins, who will spend it on other things which use energy, and so on.

The proponents of Jevon’s Paradox tell us that while it may not be obvious at first (because it’s a very complex system) in the long run, a very large number of small increases in energy usage will add up, more than offsetting the energy I originally saved. (It’s another infinite progression, akin to Zeno’s.)

However, let’s go back to that $100. The proponents of Jevons’ want us to believe that because I saved $100 worth of energy, more than $100 worth of energy will be used.

So, here’s my question, “Where’s the additional money coming from to pay for the additional energy?”

phantom power

(25,966 posts)Far as I know, it's not controversial that making things more efficient saves energy and/or resources, all other things being equal.

Jevons was pointing out that when people feel like they're saving energy, they then have a tendency to use it in new and more ways, which tends to increase the total consumption.

At least, that's my understanding of Jevons' argument.

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)You’re using the current construction of Jevons’ Paradox.

Here’s Jevons’ Paradox as stated by him:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jevons_paradox

So, let’s follow the current perversion through. (Assume my budget is perfectly balanced.) I save $100 worth of energy, giving me $100 dollars to spend on… more energy… how much more? (More than $100 worth?)

phantom power

(25,966 posts)http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jevons_paradox

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)Let’s say I cut down on my energy usage. Less demand, same supply. Therefore the price goes down (right?)

OK, since the price has gone down, I can afford to use more, and my usage goes up. (Increased demand, same supply) therefore the price goes up. (Right?)

Are you telling me that in the end, we wind up in a place where, overall, my usage goes up (increased demand) but that the price goes down (allowing me to afford to use more?)

phantom power

(25,966 posts)In other words, the end state could be that the price of the resource *does* go up, but that people are doing more different things with that resource - using it in more niches.

However, in real life all the parts are moving all the time. Note that Jevons is also talking about macro-economic effects, which includes a notion of overall economic growth over time. How does that happen? As GG discusses down below, it happens by the economy absorbing more natural resources and energy from 'the world.'

Jevons was writing near the beginning of the industrial revolution. the future was so bright, they all hadda wear shades. Energy was getting steadily cheaper, and continued to do so, until the present day, modulo noise. So the "end state" could involve more being used, at cheaper price. If we are entering a new regime where energy is going to get expensive for a long time, then maybe not so much.

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)Explain to me how I can afford to use more energy, unless the actual price of energy goes down…

phantom power

(25,966 posts)The first is economic growth, where the economy is more wealthy over time. Resource X is more expensive, but everybody has more money.

The 2nd is hysteresis combined with finite look-ahead. Efficiency increases. Resource X gets cheaper. People respond by inventing more ways to use X. More X starts to be consumed. Eventually, X gets more expensive again - oopsie! But now people are using it for more stuff. So. Maybe people shift resources from A,B,C to pay for more X. Or, like the 2000s here, they compensate with credit for a while. Eventually, maybe there's a round of demand destruction.

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)You are trying to tie a misunderstood math "paradox" (which converges absolutely) to something entirely different.

So, here’s my question, “Where’s the additional money coming from to pay for the additional energy?”

Similarly, have you asked where the additional money comes from in Keynesian fiscal stimulus that is attributed to the "multiplier effect"?

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)Jevons’ Paradox (as it is explained today) is pseudo-science nuttiness.

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)You really are not even fully critiquing the core of the paradox but questioning how an economy can infinitely increase the velocity of capital & energy from finite sums

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)It’s just another factor in the supposed “complexity of the system.”

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)Well, doy, since you say so.

It actually answers the entire crux of your real question:

Where’s the additional money coming from to pay for the additional energy?

If production creates wealth (the ability to demand energy/production), then all production at time T create additional wealth that will exist at time T2 that can potentiate further production. IOW, at time T2, there is not just $100 dollars, but also the additional wealth the initial spending of that $100 dollars creates. The is how economies naturally increase the velocity of energy.

This is very basic economic theory actually. Production multiplies tangentially outward across an economy by creating more and more wealth, that potentiates further production.

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)The truth of the matter is that (as I said yesterday) Watt’s steam engine was not simply an incremental improvement on Newcomen’s design. Watt’s engine was useful. So, it was used (kicking off the industrial revolution.)

Was it the efficiency of Watt’s design which caused more coal to be burned?

Let’s compare Watt’s engine to Edison’s light bulb. There were bulbs before Edison’s. Edison’s bulb was simply an improvement on its predecessors.

Was it the efficiency of Edison’s bulbs which led to the growth in the use of electric light?

Or, let’s compare it to Ford’s Model T. It wasn’t the first automobile. It may or may not have been an improvement on its predecessors.

Was it the efficiency of the the Model T which led to its wide use?

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)This one is fatally mangled by irrelevant topics and a discrete math problem ![]()

Was it the efficiency of the the Model T which led to its wide use?

BTW, to answer your question, probably not. Efficiency isn't *the only* thing that is going to cause wider use. Innovation and usefulness can too. This doesn't disprove Jevon's Paradox at all. Im not sure why you think it does, if you think it does.

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)You may start another if you like.

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)None of which particularly relates to Jevon's Paradox (insofar as such innovation isn't strictly efficiency related)

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)You may start your own thread if you like.

Agnosticsherbet

(11,619 posts)The Planck Length is the smallest length anything can be, and thereby makes the infinite progression of half sizes impossible. Since Planck's wallet doesn't contain a trillion dollar coin, the Jevon's paradox is bull.

wtmusic

(39,166 posts)If you define a "plancklet" as 1/2 of a Planck distance, that distance is every bit as real as a fathom or a mile.

Jevons paradox has nothing to do with convergence so it's only related to Zeno's in that both are paradoxes. A pointless comparison.

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)Essentially it comes from moving resources out of the "natural world" and inside the boundaries of the system of civilization. This includes both resource extraction and manufacturing (the infamous value added).

We define that net movement (the inflow of all new material net all degraded material - i.e. garbage) as wealth creation if the net is positive or wealth destruction if it's negative. The fiat money supply is ideally kept in balance with the net physical wealth. As physical wealth increases, the money supply increases to keep the cost per unit of wealth approximately constant. Inflation is the financial analogue of the extra energy needed to overcome the heat of friction in a physical system.

So if I spend $1000 less in a year on my lighting, that $1000 enters the economy and eventually most of it winds up being used to extract or make physical things. The part that is not used that way is dissipated as the economic equivalent of "waste heat" - my payment to the second law of thermodynamics as expressed in the system of civilization.

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)I don’t see how that follows.

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)Money becomes available to use for resource extraction or manufacturing either by fiat or by being spared within the economy through improved efficiency.

That money essentially goes to buy energy that is used in the extraction and manufacturing processes. Those processes increase the store of real wealth that then has to be reflected in the money supply. If the net wealth increase has a value greater than the money spared by efficiency, more money has to be created by fiat to cover the difference.

If we want our store of physical wealth to increase over time - to cover increases in both the world population and average standards of living - and efficiency improvements fall below the amount needed to do that (plus offsetting the "thermodynamic waste heat" of the economy - inflation), we will end up consuming more energy than we saved. We can't help but do that if we want our real wealth to grow or even stay stable, in the presence of global economic friction.

If we were to spare more money through efficiency than is required to maintain the world economy, that money will be invested and end up facilitating more extraction/manufacturing, which will consume more energy.

The second law of thermodynamics, especially in the presence of rising populations and rising expectations, turns the whole game into a canonical Red Queen's Race.

The key assumptions here are:

- "Real wealth" is created only by resource extraction or manufacturing (art and spreadsheets aren't "wealth"

;

;

- Money is at its root simply an abstraction of "real wealth"; and

- The second law of thermodynamics applies to the "energy" of the human system of civilization - i.e. money - in the same way that it applies to heat in physical systems.

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)You suggest that by my not consuming that energy, as a result, more energy will be consumed.

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)I'm now suggesting that if you don't consume that energy while still driving the same distance it will help the global economy grow. Money that is spared by improving efficiency in one area of the economy will be put to work in another. Efficiency keeps the global economy expanding because of the fungibility of money.

The economy keeps expanding because there are more and more people with ever-higher expectations for standard of living, and because we have not exhausted any key natural resources yet. It's the growth drivers of civilization that need to be addressed, because efficiency improvements do nothing but free up money for reallocation.

In this context, the mention of Jevons is probably a red herring. I think Dr. Garrett may have got it wrong as well, in the initial paper I posted yesterday. There are far simpler mechanisms to explain the increasing use of energy than appealing to Jevons.

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)Like most paradoxes, when tested, we find that it is not true.

As I have stated before, “per capita” energy use has increased pretty much since the initial use of a cooking fire.

The Model T didn’t sell so well because of its great gas mileage, it sold so well because Henry Ford made sure that his customers could afford it.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ford_Model_T

"I will build a car for the great multitude. It will be large enough for the family, but small enough for the individual to run and care for. It will be constructed of the best materials, by the best men to be hired, after the simplest designs that modern engineering can devise. But it will be so low in price that no man making a good salary will be unable to own one – and enjoy with his family the blessing of hours of pleasure in God's great open spaces."[/font][/font]

http://www.econedlink.org/lessons/index.php?lid=692&type=student

In October 1908, the first Model T Fords were sold for $950. As Henry Ford found new ways to reduce production costs, he passed the savings on to consumers as lower prices. By 1912, the car was selling for $575. It was the first time that a new car had sold for less than the average wage of U.S. workers. The price of the Model T would continue to drop during its 19 years in production, at one point dipping as low as $280. With each price cut, more and more consumers could afford to buy the cars.

This reduction in price meant that the Ford Motor Company had smaller profit margins (on each Model T), but its revenue stayed the same. How was that possible? In 1909 the profit on a car was $220. By 1914, the margin had dropped to $99. But sales were exploding. While profit margins on individual cars were smaller, the added sales volume increased total profits. During this period, the company’s net income rose from $3 million to $25 million. Its U.S. market share rose from 9.4 percent in 1908 to a remarkable 48 percent in 1914.

…

Up to this point, the lesson had focused primarily on mass production, but mass consumption was just as important to Henry Ford. His $5 day forced other employers in the auto industry and other industries to follow his lead to attract and keep workers. As a result, wages for many U.S. workers increased.

The increase in wages increased consumer demand for automobiles. The demand curve shifted right as more consumers were willing and able to buy cars.

…[/font][/font]

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)Accomplishing more work with a finite sum of energy (improving efficiency) does not tend to correlate to an economy using less of that energy source. IOW, improving the usefulness of an energy to a society does not correlate to a society using less of that energy.

Or do you disagree with that?

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)However, it may lead to the society using less energy than it otherwise would have, were it not for the increase in efficiency.

For example, I don’t believe that the increased efficiency of refrigerators inspired their growth. Years ago, I was introduced to the concept of a “beer fridge.” In essence, a new refrigerator had been bought by the family, and the old one was moved out into the garage to hold beer.

Clearly, this led to an overall increase in electrical consumption. However, the increased usage was not caused by the increased efficiency of the new refrigerator. (I don't believe the efficiency of the new refrigerator entered into the plan at all.)

However, the increased efficiency of the “new” refrigerator did lead to less electrical consumption than would have occurred, had the new refrigerator been as inefficient as the old one.

As an aside, the “beer refrigerator” scheme was inspired by the fact that the old refrigerator still worked!

http://qt.exploratorium.edu/ronh/SLOM/SLOM_0102-The_Refrigerator.m4v

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)However, it may lead to the society using less energy than it otherwise would have, were it not for the increase in efficiency.

Sure it may. But here is what you are neglecting (which relates back to the original paradox). Once a tool makes an energy more useful for growth, a society may be more inclined to use it than they were otherwise (and/or more inclined to use a tool that requires a specific energy).

If technology never allowed coal to be as useful as wood to a society, they would rarely have used it. Only at the point that some innovation makes it more useful to use coal instead wood will the society end up massively implementing the coal technology and depending on it.

Now, this isn't always true. If someone invented a bad-ass "Hummer" train that was terribly inefficient but incredibly cool, then the growth in consumption of this resource would be quite uncoupled from its efficiency.

But generally speaking the more "useful"/"inducive to growth" a fuel/thing is, this encourages it to be implemented when it may not have been before (or an alternative would of been used instead like oil eventually). Clearly though, this isn't the 1800s and we have thousands of other growing factors (some at exponential rates)

I think we are in a different world now where "efficiency gains" don't really make items consume less of a resource in actuality (there may be a points of diminishing returns where it takes more and more energy to make something just a little more efficient). But if there is ever a lower demand on an energy resource by any means (that correlates to a price reduction), the economy will evolve to utilize the surplus energy in some manner.

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)I have seen absolutely no data to suggest that “efficiency gains” lead to greater consumption.

muriel_volestrangler

(101,321 posts)Coal consumption in Britain skyrocketed when Watt invented a more efficient steam engine, and it continued to increase, as more efficient engines were developed. Other countries' production followed a similar pattern, based on when they started using steam engines.

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)It also doesn't consider cultural and socio economic trends that drive consumption (like people who bought hummers for example). I still very likely has merit in a game theory environment with more controlled variables.

The Khazzoom–Brookes postulate is much more applicable for our world in my opinion.

Basically though, I think it is generally true that the more useful energy source becomes (in terms of useful work per dollar, as determined by various tools), the more likely the economy will evolve to utilize it.

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)less fungible money etc. etc. Jevons also worked from observation in one isolated area of the economy. He applied his observations to the theory of supply/demand pricing and out popped a consistent conclusion, but one that was valid only for the situation he had observed.

What has happened since then is that the neatness of the hypothesis has attracted a lot of contrarians (me included). When they adopted it as a shibboleth they stopped short of looking into the larger issues of growth. The growth drivers of population and human wants will swamp any rebound effect, IMO.

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)Nederland

(9,976 posts)LED's produce the same amount of light with less electricity, which is an efficiency improvement. Efficiency improvements can result in people spending less time working, or the same amount of time working but getting more money. The very first efficiency improvements that came from the Industrial revolution technologies resulted in people working less. Six day work weeks were common, as well as working 10-12 hours a day. Average work hours drifted down to around 40 hours a week, then leveled off. Apparently once you get to a 40 hour work week most people (in the US at least) would rather have more money than more time. The assumption that any efficiency improvement introduced today will result in more money is therefore a reasonable one.

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)Tell me how me saving $100 worth of energy leads to me using more than $100 worth of energy.

(Are you saying that LED’s make me work more than incandescent lights because they save me money?)

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)First, how much money did you spend before you saved $100 in energy? How much time went by? You had to buy light bulbs. Those light bulbs had to be created. Resources had to be extracted to make those bulbs. Workers had to get paid who might buy their own bulbs. Maybe years go by and you break even on the investment and eventually start accumulating savings personally. Meanwhile, the lightbulb generating economy has been growing larger, demanding more energy that your efficient lightbulbs may of made cheaper (they may not have, because the initial production of them may take more energy than you are saving in the short term). Frankly, while you may be saving on energy, we may be consuming even more energy mining the resources and manufacturing the bulbs that are now being put everywhere by this larger economy.

Frankly, I think your entire argument is bunk. You are ignoring the carbon debt in the manufacturing process and how that debt (which translates to capital spent) fuels further economic growth. You are presuming using LED light bulbs reduces energy consumption; while it may reduce your immediate needs, it is not proven the production of the bulb, its capital-based purchase, the work you had to do to raise the capital, the effect of the wealth the purchase created, etc, reduces aggregate energy consumption in the larger system (so Jevon's Paradox may not even be applicable to this situation to start).

If you want to argue Jevon's Paradox, you may need to find an example that doesn't rest on so many unproven premises (such as simple usage relates to a bonafide reduction in energy consumption across a wider system). LED are not a simple efficiency change, as they cost far more immediately and require more resources and more production than a normal bulb.

A better example would be people simply switching to a lower wattage traditional bulb instead of an entirely new product, because all other variables present in the economy remain largely the same (costs, production, etc), and we could actually assume a somewhat immediate reduction in consumption; this would then set the stage for Jevon's Paradox.

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)Yes, go on…

(The result of us using lower wattage light bulbs would be…)

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)Less consumption of coal based energy -> Less demand for coal based energy -> Lower price for coal based energy (presuming a constant EROEI and no irregularities in commodity trading) -> More coal based energy could be commanded with less capital -> Coal based energy then becomes more attractive to investors and society (more work for less capital) -> Society becomes more dependent on coal based energy due to more devices created to use coal based energy -> Higher demand for coal based energy -> Higher Price for coal based energy

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)How is it that people can afford to use more (more expensive) coal-based energy, as a result of them saving some money by using less coal-based energy?

I know, I know, it’s “turtles all the way down.”

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)There is an immediate effect at T1, and then something happens at T2, that causes something to happen at T3, etc...

By the time the economy expands and consumption increases all around, there is more wealth (created via the economic expansion) to command such energy. And the people who initiated the savings are not necessarily the people who, in the end, are paying more for the energy once consumption rebounds.

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)I understand the concept, but can you demonstrate that it has happened?

i.e. Can you document an example of increased efficiency leading to increased consumption due to a (temporary) decrease in prices which then led to an increase in prices, due to continued increased consumption?

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)I can't track down the full text at the moment, but check out some of Khazzoom's work with appliances. It relates how efficiency standards actualized a higher energy usage that contradicted the predictions.

If you can do more useful work with less money (economic efficiency), it makes that work tool more efficient at growing the economy (resulting in a larger economy and a higher reliance on that tool--or energy source if it was economically transformative like the Jevon's steam engine example).

How do you believe that reality works? Seriously?

Do you believe all efficiency savings instantly, permanently translate to energy savings?

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)You need to demonstrate that increased efficiency of appliances leads to such an increase in their use that more energy is used as a result.

http://switchboard.nrdc.org/blogs/dgoldstein/some_dilemma_efficient_applian_1.html

The reality is that the increase in efficiency of appliances is a huge success story for all consumers who benefit from the savings these products provide. Refrigerator energy use was growing with a trend that would have resulted in electricity demand of about 175 GW by today; but with efficiency policies that level of power demand was cut to less than 15 GW. The difference, about 160 GW, compares to about 125 GW provided by the entire nuclear power fleet in the United States, or to 400 large coal plants that were expected to be needed but now are not.

…[/font][/font]

Appliances are used more today than they were in the past, but not because they are more efficient.

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)Im not talking about "today". Checkout Khazzoom–Brookes postulate

Its a bit more of a modern revision in our times.

Firstly, increased energy efficiency makes the use of energy relatively cheaper, thus encouraging increased use. Secondly, increased energy efficiency leads to increased economic growth, which pulls up energy use in the whole economy. Thirdly, increased efficiency in any one bottleneck resource multiplies the use of all the companion technologies, products and services that were being restrained by it.

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)Once again, show me that increased efficiency in appliances leads to greater energy consumption.

How many people do you think have said, “I never would have used a washing machine, but now that they’re so efficient, I bought one and use it all the time! Heck! I’m washing my clothes 3 times a day!”

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)Check Khazzoom, 1980, at library. Enjoy.

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)Written by: Shakeb Afsah and Kendyl Salcito and Chris Wielga* • Jan 11, 2012

[font size=3]…

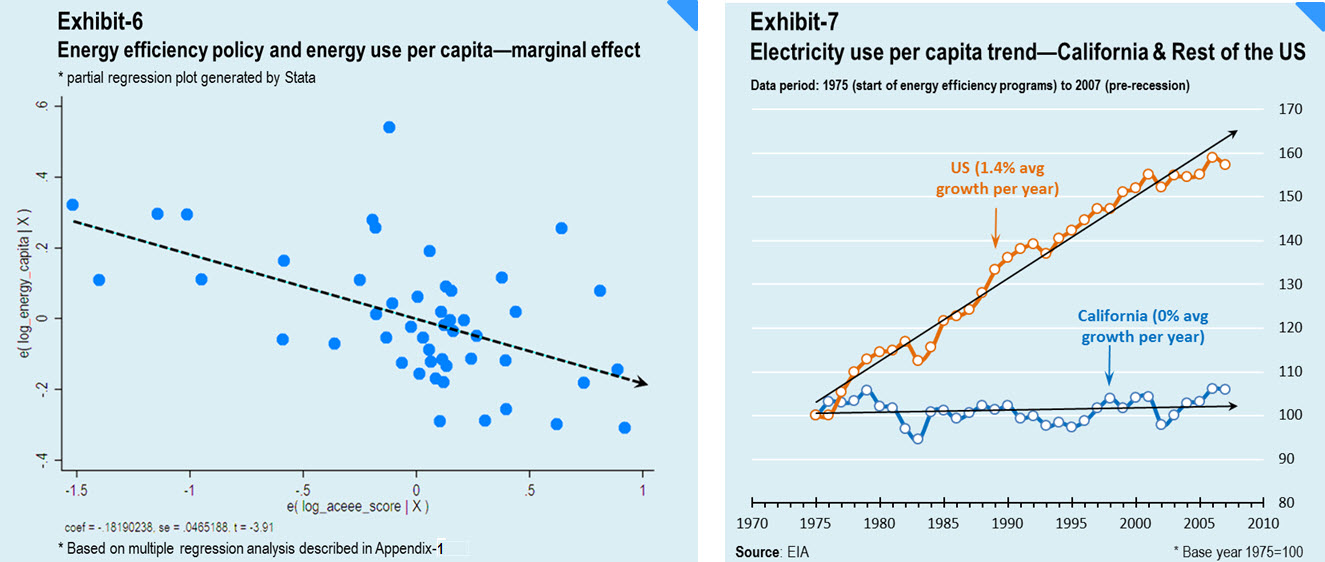

Controlling for factors like electricity and gas prices, per capita income, variations in weather patterns, population density and economic structure, we used a multiple regression model (described in Appendix-1) to statistically verify if the quality of energy efficiency policies as measured by the ACEEE is associated with lower energy use per capita.

Using ACEEE’s 2009 data, we found that a 1% improvement in ACEEE’s energy efficiency score leads to an estimated 0.18% decrease in energy use per capita at the state-level in the US. This is visualized in Exhibit-6 as a downward sloping line depicting the long run average correlation between energy efficiency policy score and energy use per capita. As discussed in Appendix 1, a similar relationship between ACEEE’s energy efficiency score and energy per capita exists for the years 2007 and 2008. This finding confirms that the causal relationship between energy efficient policies and energy use per capita is not a one-year phenomenon but is consistent and statistically significant over time.

These new findings verify what the US Energy Information Administration has been putting forth for over a decade: energy efficiency policies are central to cutting emissions. Just last year the EIA published estimates on building efficiency improvements using best available technologies, but the agency noted that even with the best technology, policies would still need to be in place to promote efficiency. Data further confirm these findings—as shown in the Exhibit-7, California, which is among the most energy efficient states and has pursued efficiency policies since 1974, was able to put a lid on the average per capita electricity consumption for over three decades—in comparison electricity use per capita increased at an annual rate of 1.4% for the rest of the US. If Rebound effects were as rampant as claimed by the Breakthrough Institute, we would not find a robust relationship between energy efficiency policies and lower electricity use per capita trend.

…[/font][/font]

Speck Tater

(10,618 posts)For example, if cars become more efficient, everybody will spend less on gas, BUT more people will buy cars because now they can afford to.

That $100 I used to spend on gas I might now spend on installing solar panels to save myself even more money, BUT, my neighbor who didn't have a car before, now goes out and buys one. It's not my $100 that gets spent on more gas. It's many other dollars spent by many other people that results in greater consumption.

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)Generally speaking, the question of whether or not a person can afford a car is based on the sticker price, not the cost of operation.

http://news.cnet.com/8301-11128_3-20057942-54.html

[font size=4]Consumers won't buy alternative power trains unless initial costs come down and misinformation about technology is corrected, J.D. Power report warns.[/font]

by Candace Lombardi | April 27, 2011 11:45 AM PDT

[font size=3]Despite rising prices at the pump, many consumers are still reluctant to purchase vehicles with alternative power trains because of cost and misunderstandings about the new technologies available.

That's according to the J.D. Power and Associates "2011 U.S. Green Automotive Study," whose primary findings were released today.

The J.D. Power and Associates study was conducted in February and included interviews with over 4,000 U.S. consumers planning to buy a new vehicle within one to five years. It estimates that alternative vehicles will make up less than 10 percent of the market by 2016 despite the plethora of models expected to become available in the coming years.

The study found that attitudes toward the adoption of alternative power train vehicles, which includes plug-in electric, plug-in hybrid, hybrid, and clean diesel engines, were mainly dependent on affordability. Over 75 percent of those consumers surveyed said the main reason they would consider an alternative vehicle car is to save on fuel. But consumers were not willing to pay a premium to be green unless it resulted in a cost benefit to them personally in the form of significant fuel savings, according to the report.

…[/font][/font]

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)Presuming the purchasing of hybrids have any substantial impact on the demand of gas (as more people become new drivers than the amount of hybrids that are purchased)

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)People generally buy based on the price of the car. The price of gasoline is a secondary consideration.

Compare this to the choice between incandescent light bulbs, CFL’s or LED’s. In the long term, it’s cheaper to install alternative bulbs, but there’s so much consumer resistance to buying “more expensive” bulbs, that governments have decided to regulate light bulb efficiency (essentially forcing people to save money against their will.)

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)The more people who drive hybrids instead of normal cars would result in decrease oil consumption (ASSUMING that we pretend hybrids don't have a higher carbon debt, which is false). So that would theoretically result in less demand for oil and then lower oil prices (ASSUMING constant EROEI and no future trading, which is false). More affordable oil makes it more easier to purchase at the pump or more attractive for fueling gasoline dependent growth. The moment oil becomes more attractive at fueling growth (less capital commands more energy), the economy will evolve to take advantage of this to become a "more efficient" economy. Of course, you are again making a ton of assumptions with that example.

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)Why do more efficient cars mean more people will buy them?

It should be:

Why do cars that reduce oil consumption eventually cause more oil to be consumed

I never suggested more people would buy the cars. My response was that if those cars lowered demand for gas/oil, then more people (other people) would be able to afford such oil. Oil would become more affordable for fueling economic growth.

Though, this also assumes those cars reduce oil consumption, when their production could increase immediate consumption.

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)—By Kiera Butler | Mon Mar. 7, 2011 2:30 AM PST

[font size=3]…

Furthermore, Matt Mattila, who leads RMI's effort to help cities transition to electric cars, points out that the limiting factor for driving isn't fuel consumption, but rather time spent behind the weel. "Drivers generally don't know their vehicles' fuel economy, but if they did see it improve, they wouldn't 'balance' that out by trying to find more time in the vehicle," says Mattila.

Building on that idea, Simon Mui, a scientist who studies electric cars at the Natural Resources Defense Council, calls the notion of attributing increased driving to gains in fuel efficiency "mind-boggling." Because of population increase, rising incomes, sprawl, and increased car ownership rates, vehicle miles traveled has gone up both in the US and abroad, says Mui. "This has happened even when fuel economy was flat (or even worsening because of SUVs) in the US over the past three decades."

Still, there's a kernel of truth to the Jevons Paradox argument. When talking about fuel-efficient cars, it's important to distinguish between the rebound effect and the backlash effect. The rebound effect—where some savings are lost because of increased use—is well-documented, and regulators take it into account: Last year, the EPA and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration assumed a 10 percent rebound effect when they made their final ruling on emissions standards. But a backlash effect—where increased car use actually cancels out any savings gained by efficiency—has never been documented.

…[/font][/font]

NoOneMan

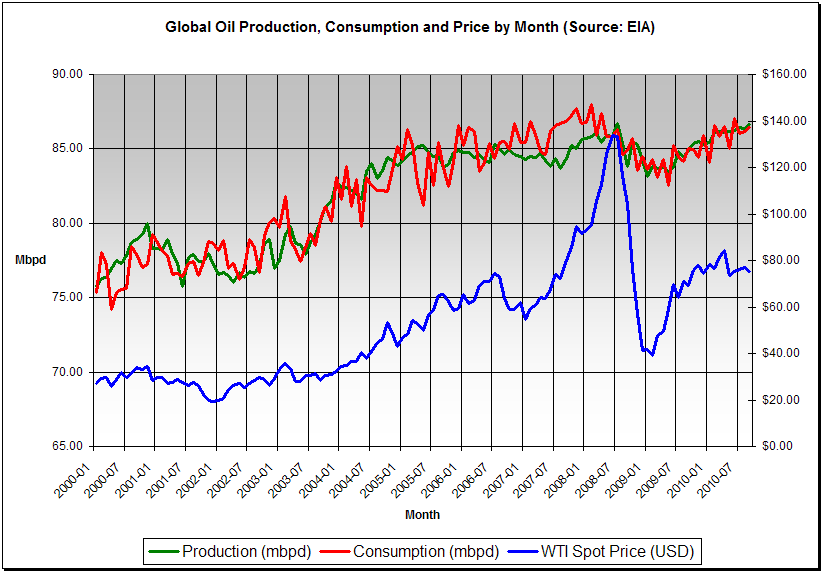

(4,795 posts)The relationship between the price of oil and demand is pretty clear (though, oil being a required fuel we now depend on, it will never operate strictly according to theoretical graphs):

http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-UmRTuUVy8ys/T5fr8J0QgCI/AAAAAAAACq4/nPPVitvqHbQ/s1600/Screen+shot+2012-04-25+at+8.17.38+AM.png

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)Over the years, oil use has consistently increased, in spite of increasing prices.

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)(as the provided graph shows)

As far as its overall price over the years, yes, its going up (despite efficiency gains that made it an even more useful fuel). What else are we going to put in our cars? Demand is constantly increasing. We need more and more of it. It takes more and more energy to bring it to market. And none of that has anything to do with Jevon's Paradox.

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)Let’s get back to Jevons. Can you demonstrate that improved efficiency leads to increased consumption?

Remember, Jevons was talking about a very specific case, i.e. a more efficient coal-fired steam engine led to increased consumption of coal by steam engines.

So, it’s up to you to demonstrate that increased efficiency of automobiles leads to greater consumption of gasoline (as opposed to a general trend toward greater consumption, independent of increased efficiency.)

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)demonstrate that increased efficiency of automobiles leads to greater consumption of gasoline

You must first prove that "efficient" automobiles like hybrids have any positive impact on oil consumption (considering first that their production takes about 113 million BTUs plus the additional consumption it requires to produce the capital to purchase one). Very likely, this example is again irrelevant to this paradox.

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)The claim is that increased efficiency causes increased consumption (rather than increased consumption simply being an ongoing trend.)

http://www.treehugger.com/corporate-responsibility/beating-the-energy-efficiency-paradox-part-i.html

Rocky Mountain Institute

Business / Corporate Responsibility

May 1, 2008

[font size=3]…

Today's popularity of more efficient vehicles and green home retrofits means it is worth seriously considering if there is evidence for Jevons' Paradox -- or even a significant rebound effect -- that could dampen some of the enthusiasm for these technologies.

Luckily, we are observing only very small rebound effects (if any at all) in the United States. For example, we can look at household driving patterns: While total vehicle miles traveled have increased 16 percent between 1991 and 2001, there is no evidence that owners of hybrid vehicles drove twice as much just because their cars were twice as efficient.

For green buildings the evidence is very similar. From many case studies related to RMI's Built Environment work, we have not seen evidence that radically more efficient commercial buildings cause people to leave the lights on all night and set their office thermostats five degrees lower. In fact, energy savings in everything from office towers to schools have often been higher than projected. People do not seem to change their behaviors simply because they have a more efficient building.

Household appliances provide the best example that efficiency gains really do stick. Take refrigerators (which can use as much as 14 percent of a household's total energy). Until the late 1970s, the average size of our refrigerators increased steadily and then began leveling off. But, during the same period, the energy those refrigerators used started to decline rapidly. Today's Energy Star refrigerators are 40 percent more efficient than those sold even seven years ago. After all, there is a maximum size to the refrigerator you can easily put in a kitchen and a limit to the number of refrigerators you need in your house. In short, improvements in efficiency have greatly outpaced our need for more and larger storage spaces.

…[/font][/font]

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)People aren't gifting you more efficient items they magically pull out of their ass. You are buying items with money you earn that need to be manufactured in the real world (which may cause more consumption and have nothing to do with Jevon's paradox)

You've bumbled through most of this thread while ignoring this.

I tried to help you with the lower wattage bulb example.

Yes, consumption does tend to increase on its own with growing wealth and growing population. But making an energy/tool more useful to a society should encourage that society to naturally use it more. That is really the bottom line of that very simplistic accounting of a real world phenomenon

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)I know that the price of oil keeps increasing overall. I asked:

Can you document that cheaper oil doesn't result in more people using oil?

IOW, when there is a significant reduction in the price of oil, does the economy react--over time--by using more of it?

To put it in the opposite manner, do quick rises in the price of oil cause less usage of oil (like less people traveling during summer because it costs more or economic contraction)?

Simple yes/no works for me.

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)You need to demonstrate that increased efficiency leads to increased consumption.

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)Demonstrate that hybrids actually lower aggregate consumption of oil first. ![]()

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)If I spend $100 less on fuel I will either use it to buy something else or I'll invest it. If I buy something else, the money goes to pay for the production of that item. If I invest it, it's used by someone else to buy something and so pays for its manufacture. Because money is globally fungible and the global marketplace in general is not saturated, growth will continue.

Actually, thinking about it a little deeper, it could be that efficiency improvements don't cause much of a a Jevons-style rebound at all, but simply keep inflation a little lower than it might otherwise be. The real culprits are growing populations and rising standards of living in the presence of 2LT - the second law of thermodynamics. No matter how much money/energy we save through efficiency, it can't cover the requirements imposed by those three factors. As a result energy consumption doesn't go down. At best it may just rise by a percent or two less than it otherwise might.

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)As well as unintended consequences.

The bottom line is that civilization grows and has perpetually increased the velocity of energy in the economic engine; that is almost its mission statement. Growing populations, standard of living and social complexity are almost always present growth inducing forces. Anything that makes one method of growth cheaper (meaning less capital can command more energy) will naturally be utilized more to increase the overall growth (and grow it surely will). It isn't the most difficult concept to grasp or observe.

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)I agree.

There are many factors at work, and a “rebound effect” may play a small role, but the notion that the rebound effect is >100% is utter nonsense.

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)Its isn't a "force". Its an explanation of market behavior and the law of unintended consequences. Its a very valid explanation as to why a fuel source may become widely used the better a society becomes at using it (because it becomes more efficient at fueling the growth that society needs).

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)By Sean Casten

Grist guest contributor

[font size=3]David Owen’s latest article ($ubreq) in The New Yorker has attracted much attention and rekindled interest in William Jevons and his paradox. Much ink has been spilled in support and opposition to Owen’s piece — a testament, if nothing else, to the quality of Owen’s prose and The New Yorker more generally.

Amidst the discussion, I’m struck that two rather obvious points haven’t been made:

- Jevons’ arguments wouldn’t pass muster in any discipline other than economics.

- Owen’s arguments fail basic principles of logic.

…[/font][/font]

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)Last edited Wed Jan 9, 2013, 06:51 PM - Edit history (2)

Do increases in energy efficiency improve environmental quality and sustainability?Jevons Paradox revisited: The evidence for backfire from improved energy efficiency

This isn't fairy tale stuff we write trendy articles about.

OKIsItJustMe

(19,938 posts)It is an appeal to logic.

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)You started with a misunderstood introductory discrete mathematics problem (that I saw on day 1 of Mathematics 106) and then related it to a paradox you don't grasp while failing to understand the notion of a multiplier effect. This thing started in tatters.

wtmusic

(39,166 posts)"By saving energy, we actually use more."

"Any attempt to save energy actually makes things worse."

"I shouldn't bother trying to save energy. Using energy is green!"

A neat mental trick. But wait, there's the inverse of Jevons:

"By saving energy, less becomes available." (It becomes less profitable to produce).

"The cost of energy rises because of scarce availability."

"My frugality has paid off. Energy costs the same as it did before, but we use less!"

There is no evading personal responsibility.

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)Its not a "why try" argument, but rather a plea to put more thought into a proposed "solution" in a complex economic system that may have unintended consequences.

Most of this thread has nothing to do with Jevon's, because the energy savings are an unfounded premise (production is not being properly accounted for). Constantly innovating new products, that require more and more energy to produce less and less efficiency savings (diminishing returns), necessitates perpetually and increased production; in such cases, the savings cannot materialize until some far off point in the future after "carbon debt" is paid down (if it ever will be). So the entire idea of "saving energy" is a moot point to discuss as we have not done that yet with a plethora of "efficient" innovations.

Of course, if you think the magical production of a green item translates to instant, immediate savings, then "save" ahead you will. If you take a moment to think about how all our actions (production and frugality) impact the system, then maybe we have a chance at plotting a sane course.

Ultimately, we need to make a wide appeal to reduce energy consumption (which efficiency savings is supposed to do in theory). If we take a very critical look at past trends, that may entail curbing production instead of producing more and more "green" things that take energy and real world resources.

wtmusic

(39,166 posts)so I have no idea what you're referring to about "more and more energy to produce less and less efficiency".

Nonsense.

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)Lets say an efficiency innovation allows you to create a product that uses 1/4 of the electricity than its predecessor. Consequently, producing this more complex product could take 16 times more energy than the simpler one, so it rolls off the assembly line with a massive amount of "carbon debt" to start. What I described is what happened with CFL.

And the impact doesn't just stop at production, as they also caused heating bills to rise from diminished heat output, cost more to dispose & ship and increases the velocity of the energy in the economy insofar as their purchase is concerned.

Believe it or not, "innovative", next generation products can require more energy to make/ship/handle/dispose than their lifespan efficiency saves, rendering their production entirely unnecessary

wtmusic

(39,166 posts)"Do compact fluorescent bulbs (CFLs) use less energy than incandescent bulbs when the energy required to make the bulbs is also considered?

Yes. CFLs use substantially less energy (and cause fewer emissions of greenhouse gases) than an equivalent incandescent even when the energy necessary to manufacture the bulbs is considered. This is for several reasons: (1) a CFL uses substantially less energy when it is on than an incandescent bulb does, 75% less, (2) one CFL will last up to ten times longer than an incandescent, so an appropriate comparison includes 8 or more incandescents for every CFL, and (3) manufacturers tell us it takes much less energy to manufacture a CFL than the energy it will use over its lifetime. ENERGY STAR recognizes CFLs based on the energy used while the bulb is on, helping consumers choose the bulb with lowest overall energy use and green house gas emissions."

http://energystar.supportportal.com/link/portal/23002/23018/Article/15103/Do-compact-fluorescent-bulbs-CFLs-use-less-energy-than-incandescent-bulbs-when-the-energy-required-to-make-the-bulbs-is-also-considered

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)Here is where it will get the edge or not: will these Chinese bulbs (shipped from China) really last as long as claimed? This is highly dependent on how you use them (leaving them on for short times impacts lifespan and efficiency). How many CFLs have you seen die early?

Also, these lifecycle assessments often fail to account for energy required to mine and refine the rare earth metals required for production as opposed to the incandescent filaments. Production does not start at the factory. Does it?

Another interesting idea is the concept of carbon intensity of production vs usage (coal vs natural gas/solar/wind). With a lot of this stuff, we pay it forward with coal by producing in the 3rd world (how "bad" is incandescent ran on wind?). This will drastically effect life-cycle assessment models if we assume carbon intensity at point of use is lower than at point of production.

And, as I briefly mentioned, we also must account for heating compensation, disposal, and economic multiplier factor (which are all not directly related to the point of diminishing returns).

BTW, there are probably much better examples of the overall concept. I think many energy-efficient home designs are plagued with diminishing return issues, where future efficiency savings can be dwarfed by production costs. You cannot forever think that efficiency gains vs production energy follows a linear line.

wtmusic

(39,166 posts)it's up to you to answer them - with data.

![]()

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)First, refer to any life-cycle assessment. Here is a quick one:

[link:http://infohouse.p2ric.org/ref/47/46011.pdf|Comparison of Life-Cycle Analyses of Compact Fluorescent and

Incandescent Lamps Based on Rated Life of Compact Fluorescent Lamp]

Use an altered assumption (because all life-cycle assessments use assumptions to create data) that the Denver, CO consumer has a solar panel. Now the production in Shanghai, China and shipment emissions are all we must consider. Edge, incandescent by the data.

The more "efficient" product must operate over a certain amount of time, with energy beyond some carbon-intense threshold, to pay its production debt back. This is sort of an interesting idea....would thorium reactors in America render CFLs obsolete to their incandescent parents?

In any case, way back to the original topic. People who say, "its complicated" might be correct. It is complicated. Both the production process and the increased economic activity (that causes GDP growth) make efficient items very complicated.

wtmusic

(39,166 posts)"These analyses of CFL and incandescent lighting’s life cycles show that the operation phase dominates both options’ CO2e impact. Therefore, the example CFL use produces fewer emissions than the incandescent. The energy benefits of CFLs have made them a realistic solution in the lighting sector."

If it's so complicated, how can you can you make any assumptions either? Should we craft policy based on preconceptions/ideology, or available data?

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)Read what I typed. If the carbon intensity drops at the point of usage (due to a solar panel), the model shows the incandescent wins.

wtmusic

(39,166 posts)You're bending assumptions to fit your ideology, and they're completely unrealistic.

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)Renewables are growing and carbon-intensity is not homogeneous (requiring different models and assumptions to make data relevant for everyone). The lower the carbon intensity of energy, the less useful these efficient items become.

wtmusic

(39,166 posts)and global warming is a societal problem.

Do you breathe your own private atmosphere? How's the weather in there?

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)But if we make this presumption, then we are all pretty much heading for disaster anyway, right?

What's it all for?

Maybe we should be more inquisitive and balanced: CFLs are better if your home runs on coal. CFLs are not better if your home runs on wind or solar.

If you are buying a CFL today and a solar panel tomorrow, you may be using more energy than sticking with the incandescents.

If you are getting a thorium reactor soon, you might want to opt-out of the production heavy low-energy home.

Somewhere along the road, its like we are told to detach our heads from our bodies and pursue Star Trek in totality without any thought of how our actions impact the system. Just look for the energy star rating and park your cognition.

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)What you argued against was this:

"more and more energy to produce less and less efficiency"

What he actually said was:

"more and more energy to produce less and less efficiency savings (diminishing returns)"

The two mean something entirely different, nicht wahr?

It's always easier to argue against someone when you trim their quotes and shape them into straw men.

wtmusic

(39,166 posts)Take your pick.

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)Hell, a hybrid uses less gas so of course a society full of them is going to emit less emissions! We don't even have to do the math! Its self-evident logic!

But in reality land, all I see is a global economy that is infinitely growing and emitting carbon at a level that--even if more efficient than a worse case scenario--is a danger to all life on earth. But we keep pretending, as we did for the last 30 years, that discussing the "goodness" of efficiency innovation/production is as silly as gravity and we need to keep plugging ahead, growing the economy with production of the latest, greatest.

In my opinion, the notion of expanding the economy with the production of innovative products to eventually lead to less consumption is entirely meaningless and unsupportable. Its what we've been doing. Where is that magic point? Why isn't it working? Is efficiency even relevant to our problem, insofar as we continue to produce and grow? Is it merely leading us to can-kick and feel better about our growing production?

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)wtmusic

(39,166 posts)i.e. ignoring data when it contradicts our worldview.

Funny you mention "the math". It shows both of you are wrong.

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)Let's analyze the actual quote: "more and more energy to produce less and less efficiency savings (diminishing returns)"

The implication of the quote iis that each successive efficiency innovation produces less of a return, because efficiency gains can only be asymptotic to 100% (or conversely that energy use can only be asymptotic to 0).

Here's an example:

In the 20 years from 1972 to 1992 refrigerator energy consumption dropped by about 1200 kWh/year, or about 60%. In the following 20 years from 1992 to 2012 consumption dropped by only 250 kWh/year, or 33%. The energy savings are diminishing over time, even as the efficiency keeps increasing.

NoOneMan

(4,795 posts)Maybe people enthusiastic about technology, innovation and efficiency say:

"Well great, we can keep increasing production with our increased efficiency until it magically translates into less aggregate consumption"

IOW, the idea of producing efficient items reinforces the myth that we can continue business as usual without fundamentally altering human institutions. The problem is this magic point where consumption goes down isn't materializing and may not at all. We just see constant growth and growth. Maybe it would be more growth without efficiency, but maybe not. In any case, its bad enough as it is that we have a disaster on our hands. The promise of this magic point isn't coming. Maybe we need to stop focusing on producing efficient items, and rather on controlling growth and reorganizing society.

Efficiency promises we don't have to change how we interact with the world so much. Its leading us to kick the can down to road until the number suddenly work out in our favor. It hasn't been happening. Maybe its time to stop kicking the can, and do what we can to reduce emissions immediately (like take a bus or walk instead of buy a hybrid, etc).

If anything, I see the pro-efficiency arguments having to do more with society evading responsibility for dealing with its production problem (it pretends that if it exists even, it will magically be solved with more production).

GliderGuider

(21,088 posts)Seen in that context, efficiency isn't any kind of a solution to the problem.

wtmusic

(39,166 posts)They prove optimism has no solution. ![]()

Peace Patriot

(24,010 posts)...and most Americans and most people in the world (except those with leftist governments such as Venezuela, Brazil, Bolivia, Ecuador, Uruguay and others in Latin America).

As we try to cross the room, from our births to our deaths, working more and more for less and less pay (if we can find work at all), seeking educations that cost more and more and MORE and that throw us into lifelong debt, paying into Social Security all the while to find our benefits, at retirement, way, WAY behind inflation, with yet more cuts intended by vicious politicians who don't represent us (were (s)elected by ES&S/Diebold and their 'TRADE SECRET' code), who find our Social Security checks dunned for Medicare but not for all of Medicare, leaving us to come up with 20% of hugely inflated medical costs while getting even LESS of our Social Security pension, should we get ill or disabled by old age, finding the cost of running the vehicles to which we have been deliberately addicted rise higher and higher and HIGHER for no reason at all ($4 frigging dollars per gallon! Jeez!), finding the costs of all energy and other essential life commodities getting beyond our reach, unable to put food on the table, unable to buy our kids Christmas presents let alone diapers, clothes, proper nutrition, books, sports uniforms, musical instruments, educational trips and all the tacked on costs of public education (if their schools even have sports any more, or orchestras, or teachers), some of us unable to even put a roof over their heads...

...and on and on, while the rich beat us along our way and take large chunks out of our flesh, as we try to cross the room (live our lives), with dreams of "putting a little away" for our kids, or "putting a little away" for that trip to Hawaii that we've put off for decades, while we worked more and more for less and less pay (if we can find work at all) gone up in smoke. No dreams any more--not even modest little dreams, like paying off the mortgage before we die and our kids inheriting the house free and clear. All gone.

We reach the middle of the room and find that we have gotten nowhere. We try to make the next couple of steps and find ourselves being pushed backwards. Zeno comes into play--logic's biggest joke come true, in real life, in 21st Century America and other places run by transglobal corporate monsters and the 1%. Most people will die, become sick or disabled, or "get kicked off the island" before they even get a chance to approach the middle point of the second half of the paradox, because, to the transglobal corporate monsters who rule over us, and the 1% who support them--getting richer and richer, while the rest of us get poorer and poorer--we are not really people; we are lines on a graph, where our modest gains go down and down, and their ungodly wealth goes up and up.

It is no surprise at all that these same forces have lied to us, time and again, about "saving energy" or "saving money" (har-har) and it is no surprise that, whatever we do, energy and other life essentials, and everything that energy produces, will cost more and more, as our incomes decline. That is the "Zeno's Paradox" of this horrible system of Corporate Rule--a philosopher's joke made manifest.

Whether Zeno's Paradox applies to "energy efficiency" in this system is pretty obvious to me. It does. But not in the way discussed (and argued about) above. It is applicable in this way: The profits of the few go up as the viability of Planet Earth goes down. These two things are tied to each other, inversely. And any effort to get past the half way point, and to start putting the decline of Planet Earth in reverse, is impossible until we STOP the profits of the few from GOING UP as the result of their extremely destructive behavior--whether it is deforestation or frakking or oil spills or oil wars, or their imperiling the food system with GMOs and pesticides, or their vast plastics pollution, or their growing of tasteless, messed-with strawberries in Chile and flying them to Los Angeles, or their avoidance of environmental laws by manufacturing in China, or their de-funding of the EPA, or their assault on every resource agency in the country and in other countries where they can get at them, or their slave labor palm oil farms and (you heard it here first) GMO marijuana farms in Colombia, or any of their other goddamn schemes to subvert democracy and workers' rights and destroy the very planet we live on, for more and more and MORE profits for the few.

We can't really tinker with this--by introducing better light bulbs or better cars--and testing out this or that economic paradox. And we CANNOT solve it as individuals, nor as isolated communities, because WE DON'T HAVE TIME. Even if we were to convert the entire USA to less individual consumption and to growing vegetable gardens instead of lawns, these powers go elsewhere--they are already there--to Asia, to Africa, to the parts of Latin America that they've been able to hold onto, not to mention the Middle East, forcing and bribing and encouraging them down the same utterly unsustainable path that we have trod. We really have to grab these Destroyers by the throat, and start deconstructing their corporations--pulling their corporate charters, dismantling them and seizing their assets for the common good.

How do we do that? First of all, we must understand that it is doable and that it is our right, as a sovereign people. Second, GET RID OF THE CORPORATE-CONTROLLED 'TRADE SECRET' VOTING MACHINES. You want to see a miracle happen to our dying democracy? That's where to start. Thirdly, we need a much bigger "Occupy" coalition, involving all the hurting people in the country--the poorly paid, the out of work, the hurting old, the hurting young, middle classers sinking into poverty, worthy professionals who hate injustice and can't do their jobs in the ethical way they would like to (doctors, nurses, teachers, fire fighters, first responders, police, social workers, et al) or whose unions are getting busted, and so on. The coalition might even include some Republicans who believe that votes should be counted in the PUBLIC venue and Corporate Rule has destroyed "main street" businesses.

This takes time we don't have too--a political coalition to END Corporate Rule--but I think it would be easier than weening Americans from over-consumption. For one thing, if your piece of crap appliance, manufactured in China, falls apart in a year, or doesn't work at all, you pretty much have to buy another. With stinking corporate policies like "planned obsolescence" and utter lack of accountability, and with millions and millions of people dependent on an urban or suburban lifestyle (can't grow their own foods or don't know how to; have long commutes, etc.), you can't just overturn these dependences overnight. A political coalition of the majority--all the hurting people in the country--while also difficult, could occur a lot faster--and could do what I've proposed here--END Corporate Rule--provided that its targets are very pointed and focused--for instance, on the 'TRADE SECRET' voting machines (for starters). Another powerful action could a boycott of all products made out of the country, or out of specific countries with obnoxious labor and/or environmental policies. However, I think political power is more important, in the near future, for saving Planet Earth--the power to start pulling corporate charters--and that requires vote counting in the PUBLIC VENUE.

Why do you think Congress has the approval rating of a dead skunk? Because a great many of them WERE NOT ELECTED. They have NO right to the power they wield. We've got to change that first--and the first step toward changing that is restoring a PUBLIC vote count. We could start ending Corporate Rule and saving Planet Earth in the next congressional elections, if we had a PUBLIC vote count.

We don't have one now. Why is that? How is it that ONE, PRIVATE, FAR-RIGHTWING CONNECTED CORPORATION--ES&S, which bought out Diebold--now controls 75% of the voting machines in the USA, using 'TRADE SECRET' code--code that the public is forbidden to review--and with half the states in the country doing NO AUDIT AT ALL of these machines?

How is that? Why is that? Think about it. And don' worry so much about Zeno and lightbulbs. Our problem--and the peril to Planet Earth--goes way beyond what products are best or what effect they might have.

Just to say: I don't discount the potential power of ideas to spread among the collective populace--ideas such as walking, bicycling or taking mass transit (if you have it), or growing your own food or buying from local farmers (if that's possible), or using less paper, plastic and energy. And I greatly admire and approve of those who are implementing these and other such ideas, and who are helping to make them popular. But I think that such movements are chancier, and more difficult for most people to implement, than restoring our rightful political power, which would appeal to most sectors of society immediately. I mean, who wants Exxon Mobil and Chevron fixing gas prices? Who wants their appliances made in China? Who wants their town destroyed and their jobs outsourced? Who wants usurious credit card rates? Who wants trillions of our tax dollars going to transglobal banksters and the transglobal Pentagon for its resource wars? Who wants their votes 'counted' with 'TRADE SECRET' code? (or who would want it if they knew about it?)

The answer to all of these questions is: Almost nobody! And the same parties who are inflicting us with these and other ills are the ones destroying Planet Earth. We have common cause among all of the people inflicted with these ills, whether they are aware of, or care about, the peril to Planet Earth, or not. That is why I think that regaining our rightful political power, as a People, is a quicker route to saving the Planet than trying to change consumer habits, dickering with consumer products or trying to make "the Market" (controlled by the transglobal corporations) 'respond' to the Planet's dire peril--or trying to transform entire cities and suburbs, containing billions of people, into "green zones." It can't happen soon and even if it did, what of these transglobal corporations' transglobal activities? We need People Power--we need a strong, vibrant democracy--to curtail their power, starting here, where most of them are chartered by U.S. states and where congress could seriously curtail them as well, if only we had a congress that represents us.