Religion

Related: About this forumFrom the Golden Calf to Gezi park: religious imagery and modern protest

Religious images have caused conflict for centuries. Turkey is now struggling with a religion too confident in its representations

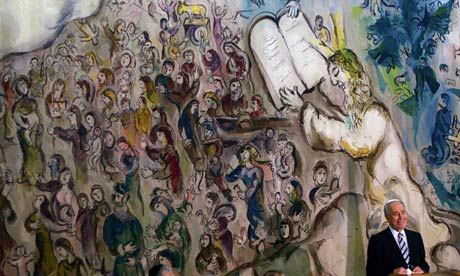

Shimon Peres in the Chagall hall of the Knesset. Behind him, Moses receives the Ten Commandments, as envisaged by Marc Chagall. Photograph: Jim Hollander/EPA

Giles Fraser

The Guardian, Friday 14 June 2013 14.40 EDT

It is extremely odd that Marc Chagall – originally Moishe Shagal – has become the poster boy of Jewish art because his work so spectacularly offends against the fundamental principle of all Jewish aesthetics, the second of the Ten Commandments: "You shall not make for yourself a sculptured image or any likeness of anything that is in the heavens above or in the earth below" (Exodus 20:4). Just because his work, currently on show at the Tate Liverpool, depicts a colourful romanticised Fiddler-on-the-Roof view of Russian shtetl life, that doesn't make it Jewish. From an orthodox perspective, it counts as idolatry, the No 1 thought crime of the Hebrew Bible. Representations are dangerous, the Bible warns. They collapse reality and come to have an independent life of their own. And when they are representations of the divine, this is especially dangerous. God cannot be pictured. Indeed G-d cannot even properly be spoken.

Chagall may have been named after Moses, but they share a fundamentally different idea about representation. For when Moses rails against the construction of the Golden Calf, he wasn't giving a go at his people worshipping something golden. It wasn't an early warning against the evils of Mammon. The problem was that it made the divine into some sort of object or thing. But as his experience collecting the Ten Commandments up on the mountaintop demonstrated, the closer one gets to the divine, the less clear things are. The higher up the mountain one gets, the more the cloud comes down and the less one is able to see. It was an early warning about the dangers of religion. Those who think they know what God is like, what God looks like, are likely to pocket the power of religion and employ it in the service of some pet cause or some political undertaking. In principle, Islam and Judaism both have access to this suspicion. The real divine is the ultimate principle of deconstruction.

Somewhen in the late 720s, the Byzantine emperor Leo III, himself a Christian, ordered the removal of a representation of Jesus from the entrance to the Great Palace of Constantinople. It sparked decades of war between those who thought images important, the iconodules, and those who thought they were dangerous, the iconoclasts. The iconodules argued that because God became human in the person of Jesus, representations of God in Christianity were acceptable (think Chagall's images of the crucifixion). Eventually, the iconodules won – although a strong minority report re-emerged at the Reformation. Hence, for instance, Cromwell's smashing of church statues. This minority report is not anti-art; it is a warning against the dangers of religion, a warning against what the Marxists would later call reification, the deathly move whereby something living is turned into something dead, into a thing.

Fast forward from the eighth century to the present day, and the city of Constantinople is in conflict again – although, of course, we now know that city as Istanbul. And the relationship of religion and politics is again at the heart of the matter. The proximate cause of the protests is the protection of Gezi park. But the deeper issue is the protection of Turkish secularisation – the protection of individual freedom against a version of religion that has become too confident in its own representations and has not properly understood the principle of divine deconstruction. When this happens, idols need to be smashed. From Occupy outside St Paul's to Gezi park, that is the theological basis for supporting protest. God is not some thing that can be wielded out and beaten into the shape of a national polity or political programme. Such a god is an idol. The book of Exodus is a source of genuine wisdom on this. The real divine constantly disturbs religion and religious politics, often aggressively so.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/belief/2013/jun/14/images-conflict-constantinople-gezi-park